“Amateurs hack systems, professionals hack people.” – Bruce Schneier, American cryptographer and writer.

Abstract

Spear phishing is a growing attack vector in critical infrastructure sectors. The majority of cybersecurity literature focuses on presenting technical solutions to technical problems; due to the complex nature of this type of social engineering attack (which encompasses both technical and non-technical aspects), spear phishing has largely been ignored in cybersecurity literature. Existing literature has shown training exercises alone to be ineffective. When applied using a rigorous methodology, Action Research, a means by which action and research can be achieved concurrently, can produce relevant results for the researcher-practitioner in addressing a real-world problem. When combined with a mixed method (or multi-method) approach, both qualitative and quantitative data can be generated that provide insight into the required course of action to minimize the number of successful attacks. Given the evolving complexity of spear phishing and the constraints of each organization, mixed methods action research (MMAR) is proposed as a viable approach for organizations to improve their cybersecurity through generating insights that extend “beyond the numbers.” This paper contributes to the literature by identifying one area that currently defies traditional research approaches (spear phishing) and demonstrating that MMAR has the potential to help organizations address this real-world problem while generating new research insights.

Introduction

A real-world problem that currently defies traditional research is spear phishing. Phishing is a type of social engineering attack, the purpose of which is to entice people into sharing sensitive information such as their login and credentials to personal accounts or providing access to their computer systems. It is most often achieved through sending emails requesting the recipient visit fraudulent web sites, open infected attachments, or prompting them to install (malicious) software on their computers. Spear phishing is defined as a focused, targeted attack via email on a specific person or organization, with the goal to penetrate their defenses (Sjouwerman, 2015). A more targeted attack is Business Email Compromise (BEC), also referred to as whaling, human hacking, or CEO fraud, where a carefully crafted message – a “spear” is sent to a specific employee at an opportune moment (Yu, 2016).

As more data breaches occur and critical information falls into the hands of potential spear phishers, it becomes increasingly easy to target specific entities and individuals. A data breach, announced in 2015, targeting the records of “all personnel data for every federal employee, every federal retiree, and up to one million former federal employees” (up to 18 million) held by the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM) has resulted in the compromise of information that ideally positions spear phishers to identify and target government personnel (Perez & Prokupecz, 2015). The information lost in the breach includes security clearance interview information, which for higher levels (secret, top secret, and beyond) necessitates that the interviewees (employee and their references) disclose sensitive information that could be used for blackmail at a later date. This presents a real risk to any organization, as information that only a trusted source may have access to can be used in a spear phishing campaign to create increasingly focused and thereby effective attacks, whether the objective is convincing a CFO to wire money to a foreign country (Hubbard, 2015), steal sensitive research and development information (Gallagher, 2011), or other nefarious activities.

The Problem: Spear Phishing

Spear phishing attacks are often successful because they send customized, seemingly credible emails that appear to come from a trusted source. To increase the likelihood of success, these attacks are generally completed after careful research on the target (Parmar, 2012). Purkait (2014) conducted a comprehensive literature review, analyzing 16 doctoral theses and 358 papers related to phishing based on their research focus, empirical basis on phishing, and proposed countermeasures. The findings by Purkait (2014) reveal

[…] different approaches proposed in past are all preventive by nature. Phishers continually target the weakest link in the security chain, namely consumers, in their attacks. Various usability studies have demonstrated that neither server-side security indicators nor client-side toolbars and warnings are successful in preventing vulnerable users from being deceived (Purkait, 2014: 407)

This is due to: phishers being able to convincingly imitate the appearance of legitimate web sites; users tending to ignore security indicators or warnings; users not necessarily interpreting security cues appropriately (Purkait, 2014).

Spear phishing is a significant issue in critical infrastructure environments. In fiscal year 2014, ICS-CERT received 245 incident reports, of which spear phishing accounted for 17% of the known access vectors; a value that increased to 37% in fiscal year 2015 (Department of Homeland Security, 2014; ibid., 2015). Despite the reports that identify spear phishing as the single largest attributable access vector identified in two consecutive years, the two guidance reports provided by the Department of Homeland Security focus exclusively on technical protection issues and solutions. The paper “Seven Steps to Effectively Defend Industrial Control Systems”, published in 2015, presents seven strategies that can be implemented to counter common exploitable weaknesses in “as-built” control systems, none of which address reducing spear phishing attacks. A passing reference to security training is buried within the paper “Recommended Practice: Improving Industrial Control Systems Cybersecurity with Defense-In-Depth Strategies” (2009), advising that CI operators should leverage “common security awareness programs, such as those listed in NIST SP800-50, Building an Information Technology Security Awareness and Training Program,” while acknowledging that “Formal training can often be cost prohibitive, but good information can be gleaned from books, papers, and websites on cyber and industrial control systems security” (Department of Homeland Security, 2009: 27).

Recent research has indicated that most security training is insufficient; it occurs infrequently (annually) and the effect of the training is often lost in as little as 28 days (Kumaranguru et al., 2009). In 2010, the Institute for Information Infrastructure Protection (I3P) initiated research that addressed ways to accomplish two key industry goals: reduce the vulnerability to spear phishing by training employees to recognize it, and improve an organization’s “security culture” by encouraging employees to report spear phishing incidents (Caputo et al., 2014). The research consisted of deploying a test spear phishing email and providing immediate embedded training if the recipient failed the test (clicked on a link in the email). While the majority of interviewees believed that the kind of embedded security awareness and training employed in the study is more effective than the once-yearly mandatory training they received, the study indicated immediate feedback and tailored framing were insufficient in reducing click rates or increasing reporting (Caputo et al., 2014).

A Potential Solution: Mixed Methods Action Research (MMAR)

Action research (AR) is a generic term which covers many forms of action-oriented research. It is referred to by multiple names, including: participatory research, collaborative inquiry, emancipatory research, action learning, and contextual action research. The outcomes are both an action and research, unlike traditional positivist science which aims at creating knowledge only. Described as “an interventionist approach to the acquisition of scientific knowledge that has foundations in the post-positivist tradition” (Baskerville & Wood-Harper, 1996), AR aims to “solve current practical problems while expanding scientific knowledge” (Myers, 2009:59).

The concept of “action research” is surprisingly old; Kurt Lewin, a German-American social psychologist and educator, is generally credited as the individual to first coin the term “action research” when describing his work in the mid-1940s. In the mid-1950s, action research was attacked as “unscientific, little more than common sense, and the work of amateurs” (McFarland & Stansell, 1993: 15). Action research suffered a further decline in favour during the 1960s because of its association with radical political activism (Stringer, 2007:9). As experiments with research designs and quantitative data collection became the norm, general interest in action research waned. Action research re-emerged in education and social sciences research during the 1970s, as practitioners questioned the applicability of scientific research designs and methodologies as a means of solving education issues. This shift in perspective was the result of many federally funded projects which were seen as theoretical, and not grounded in practice. AR has since moved into other areas where researchers-practitioners wish to solve real-world problems and generate new knowledge concurrently; action research for organizational science has begun to appear as recently as this century (Coughlan & Coghlan, 2002).

Coughlan & Coghlan (2002) reviewed the work of multiple authors in order to create a list of four broad characteristics of action research: (1) it focuses on research in action, rather than research about action; (2) it is participative; (3) it is research concurrent with action; and (4) it is both a sequence of events and an approach to problem solving (Coughlan & Coghlan, 2002:202). Westbrook (1995) presented AR as an approach that could overcome three deficiencies associated with traditional research topics and methods: (1) it has broad relevance to practitioners; (2) it has applicability to unstructured or integrative issues; and (3) it can contribute to theory. In summary, the desired outcomes of AR approach are “not just solutions to the immediate problems but important learning from outcomes both intended and unintended, and a contribution to scientific knowledge and theory” (Coughlan & Coghlan, 2002:203).

Action Research is often associated with a pragmatic worldview; namely, using whatever approach best aids the researcher. Pragmatism is often associated with mixed methods (Creswell, 2009); thus, the use of a mixed methods approach in action research is often appropriate. Action research studies that employ both quantitative and qualitative research methods within a mixed methods approach are referred to as Mixed Methods Action Research (MMAR) studies (Ivankova, 2014). Mixed methods research is research “in which the investigator collects and analyzes data, integrates the findings, and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study or program of inquiry” (Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007:4), and differs drastically from the mono-method approach of employing either quantitative or qualitative methods. Some individuals argue that it is inappropriate to integrate quantitative and qualitative methods due to fundamental differences in the philosophical paradigms underlying those methods – this belief that the two methods are incompatible is commonly referred to as the incompatibility thesis (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). The fundamental principle of mixed methods research implies, contrary to this belief, that “methods should be mixed in a way that has complementary strengths and non-overlapping weaknesses” (Johnson & Turner, 2003: 299). Many of the concerns of incompatibility theorists can be addressed through adjusting the relative importance of the quantitative and qualitative methods through modifications to priority or weighting, for answering the study’s questions (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009).

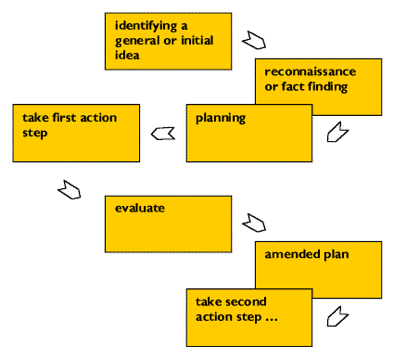

The linking of the terms action and research highlight the essential features of MMAR (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988). Typically, action research is characterized by spiralling cycles of problem identification, systematic data collection, reflection, analysis, data-driven action taken, and, finally, problem redefinition. Lewin (1946) described the process as cyclical, involving a “non-linear pattern of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting on the changes in the social situations” (Noffke & Stevenson, 1995:2). His approach involves a spiral of steps, “each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action and fact-finding about the result of the action” (ibid.: 206). The basic cycle is depicted as follows:

Figure 1 Lewin Action Research Spiral circa 1946

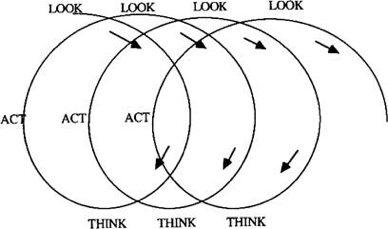

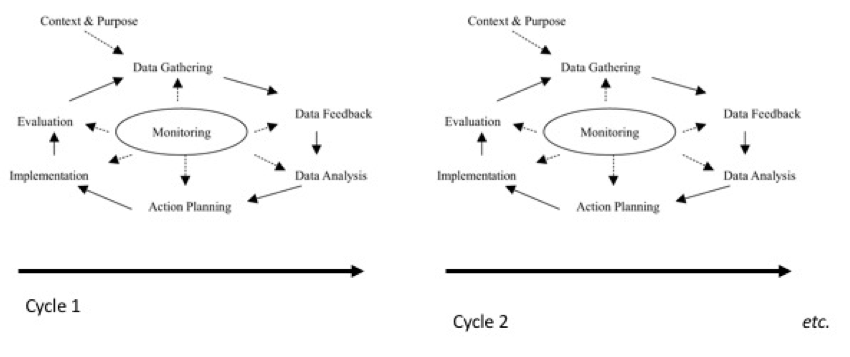

This process has been refined by multiple researchers, resulting in many action research spirals now being available to researchers (Smith et al., 2007). They are generally canonical in that the cycles are repeated until minimal additional insight can be generated and the researcher deems the project complete (Ivakova, 2015). The processes range from the simplistic look-think-act AR spiral put forward by Stringer (1999) (Figure 2), through to the rigorous and complex AR spirals, such as the model put forward by Coughlan & Coghlan (2002) (Figure 3).

Figure 2 – Look-Act-Think Action Research Cycle (Stringer, 1999)

Figure 3 – Canonical Action Research Cycle (Adapted from Coughland & Coghlan, 2002)

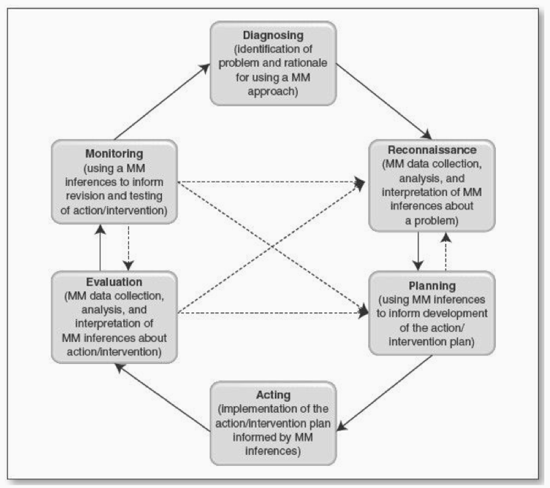

The diversity in theory and practice among action researchers provides a wide choice for potential action researchers as to what might be appropriate for their specific research question (Reason & Bradbury, 2001). Although the number of stages can vary, a five-stage model of (1) problem diagnosis, (2) action planning, (3) action taking, (4) evaluation, and (5) learning is common in AR cycles (Baskerville & Wood-Harper, 1998). The most recent and comprehensive spiral is that of Ivankova (2014) (Figure 4). It follows a similar format, showing the canonical approach to the research, which ideally continues until no further information can be generated and the research objectives have been met.

Figure 4 – Mixed Methods Action Research (MMAR) cycle (Ivankova, 2014)

Problem + Solution: MMAR and Spear Phishing

As noted above, spear phishing – particularly attacks against critical infrastructure – is a real-world problem that currently cannot be solved using a traditional, positivist research approach. A MMAR approach would be ideal, as qualitative and quantitative methods will likely generate the insights required to adapt internal training to help reduce click rates on spear phishing emails. Repeating the I3P approach using an action research cycle would allow researchers the opportunity to test different variables based on the insights generated through each cycle. More specifically, the ability to conduct a test spear phishing campaign, analyze the quantitative results (click rates), and seek out qualitative input (interviews with individuals who clicked). This would be research in action, rather than research about action, it would be participative (research performed with the participants, not on the participants), the research would be concurrent with action, and it would be both a sequent of events and an approach to a problem – thus meeting the characteristics as identified by Coughlan & Coghlan (2002). Using the stages proposed by Ivankova (2014), a possible research approach would be as follows:

| Phase | Phase Description | Action Items/Outputs (Example) |

| Diagnosing | Practitioner-researchers conceptualize the problem that requires solution in the workplace or other community setting, and identify the rationale for investigating it by using both quantitative and qualitative methods (Ivankova, 2014). | Action items: · Carefully craft a question (or multiple questions) that permits the investigation of this issue in a format that permits both action and research. · Determine which mixed methods designs are most appropriate for resolving the issue of spear phishing for organization. · Provide rationale for investigating it using both qualitative and quantitative methods. Outputs: · Qualitative interviews with employees at all levels will help to obtain insight into problems · A quantitative survey would help obtain insight into actual understanding. · Argument that the two methods – whether concurrent or consecutive – will provide more insight than a mono-method approach. |

| Reconnaissance, or fact finding | Preliminary assessment of the identified problem or issue is conducted using mixed methods in order to develop a plan of action/intervention (Ivankova, 2014). | Action items: · Conduct a literature review · Outline the current understanding regarding issues related to spear phishing within organization. Outputs: · Preliminary assessment using qualitative or quantitative measures. Review of facts identified in order to develop a plan of action/intervention. |

| Planning | Action/intervention plan is developed based on mixed methods inferences from the reconnaissance phase (Ivankova, 2014). | Action item: · Action/intervention plan is developed. Output: · An action / intervention plan that models the I3P approach, whereby a test is issued and the results are followed up via qualitative interviews. · Supplemented with additional training, to build on pre-existing knowledge re: poor retention of spear phishing training. |

| Acting | Action/intervention plan is implemented (Ivankova, 2014). | Action items: If I3P model is followed: · Deploy a test to generate quantitative results. · Split testing of group receiving supplemental training vs. no training. Outputs: · Data regarding efficacy of Group A (training) vs Group B (no advanced training) |

| Evaluation | Action/intervention is evaluated using mixed methods to learn whether it produces the desired outcomes (Ivankova, 2014). | Action items: · Follow up with interviews to generate qualitative insights regarding the efficacy of spear phishing campaigns. · Review insights generated through the campaign (both via qualitative and quantitative data) Outputs: · Educated opinion on efficacy of the current action/intervention plan and if it needs adjustment. |

| Monitoring | Practitioner-researchers make decisions about whether the revisions or further testing of an action/intervention plan is needed based on mixed methods inferences from the evaluation phase (Ivankova, 2014). | Action items: · Determine whether revision or further testing is needed (ie. has the click-rate of spear phishing campaigns been sufficiently reduced, or is additional and/or different training / intervention required?) Outputs: · If additional research is required, inferences from the evaluation phase are used to determine the next course of action. |

Conclusion

Mixed Methods Action Research (MMAR) is an approach that has not been utilized to better understand the field of cybersecurity or cybersecurity training. MMAR could be a good fit for solving the issue of spear phishing; the cyclical approach that combines both qualitative and quantitative methods would allow a practitioner-researcher to develop a solution suitable for their environment while generating valuable knowledge for broader application in relation to cybersecurity problems.

This article serves to provide one more tool for a researcher to consider when determining what approach is best suited to their environment. It has potential to be a good fit with complex problems that have not been solved using a positivist approach, such as spear phishing. It is likely that if applied in the above mentioned scenario, it would meet the overarching objective of solving a current practical problem while expanding scientific knowledge (Baskerville & Myers, 2004).

There are limitations to this discussion; specifically, it is theoretical in nature. While this article may provide the foundation for a potential MMAR study in cybersecurity, it does not provide these insights or a solution. Cybersecurity managers and trainers are encouraged to consider this approach when approaching real-world problems that cannot be addressed using traditional, positivist research.

References

Baskerville, R., & Myers, M. D. 2004. Special Issue on Action Research in Information Systems: Making IS Research Relevant to Practice: Foreword. The Mississippi Quarterly, 28(3): 329–335.

Baskerville, R. L., & Wood-Harper, A. T. 1996. A critical perspective on action research as a method for information systems research. Journal of Information Technology Impact, 11(3): 235–246.

Caputo, D. D., Pfleeger, S. L., Freeman, J. D., & Johnson, M. E. 2014. Going Spear Phishing: Exploring Embedded Training and Awareness. IEEE Security Privacy, 12(1): 28–38.

Coughlan, P., & Coghlan, D. 2002. Action research for operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 22(2): 220–240.

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. 2011. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications Inc.

Creswell, J. W. 2009. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods. Los Angelos: SAGE Publications.

Evan Perez and Shimon Prokupecz, C. 2015, June 22. U.S. government hack could actually affect 18 million. CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2015/06/22/politics/opm-hack-18-milliion/index.html

Gallagher, S. 2011, November 1. “Nitro” spear-phishers attacked chemical and defense company R&D. Ars Technica. http://arstechnica.com/business/2011/11/nitro-spear-phishers-attacked-chemical-and-defense-company-rd/.

Hubbard, R. February 5, 2015. Impostors bilk Omaha’s Scoular Co. out of $17.2 million. Omaha.com. http://www.omaha.com/money/impostors-bilk-omaha-s-scoular-co-out-of-million/article_25af3da5-d475-5f9d-92db-52493258d23d.html.

Ivankova, N. V. 2014. Mixed methods applications in action research: From methods to community action. SAGE Publications.

Johnson, B., & Turner, L. A. 2003. Data collection strategies in mixed methods research. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research, 297–319.

Kumaraguru, P., Cranshaw, J., Acquisti, A., Cranor, L., Hong, J., et al. 2009. School of Phish: A Real-world Evaluation of Anti-phishing Training. Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, 3:1–3:12. New York, NY: ACM.

Lewin, K. 1946. Action Research and Minority Problems. The Journal of Social Issues, 2(4): 34–46.

McFarland, & Stansell. 1993. Historical perspectives. In L. Patterson, C.M. Santa, C.G. Short, & K. Smith (Ed.), Teachers Are Researchers: Reflection and Action. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

McTaggart, R., & Kemmis, S. 1988. The action research planner. Deakin University.

Myers, M. D. 2013. Qualitative Research in Business and Management. SAGE Publications.

Noffke, S. E., & Stevenson, R. B. 1995. Educational action research: Becoming practically critical. Teachers College Press.

Parmar, B. 2012. Protecting against spear-phishing. Computer Fraud & Security, 2012(1): 8–11.

Purkait, S. 2012. Phishing counter measures and their effectiveness – literature review. Information Management & Computer Security, 20(5): 382–420.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. 2001. Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. SAGE Publications.

Sjouwerman, S. 2015. Confronting “Spear Phishing” Etc. Privacy Journal, 41(7): 3–4.

Stringer, E. T. 2007. Action Research, vol. 4th Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. W. 2007. Editorial: The New Era of Mixed Methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1): 3–7.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. 2009. Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. SAGE Publications Inc.

Westbrook, R. 1995. Action research: a new paradigm for research in production and operations management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 15(12): 6–20.

Yu, R. 2016, April 6. Cyber criminals go spear phishing, harpoon executives. Third Certainty. http://thirdcertainty.com/infographics/cyber-criminals-go-spear-phishing-harpoon-executives/.

Yue, C., & Wang, H. 2010. BogusBiter: A Transparent Protection Against Phishing Attacks. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology, 10(2): 1-31.

ICS-CERT Monitor. November-December 2015. Department of Homeland Security. https://ics-cert.us-cert.gov/sites/default/files/Monitors/ICS-CERT%20Monitor_Nov-Dec2015_S508C.pdf.

Recommended Practice: Improving Industrial Control Systems Cybersecurity with Defense-In-Depth Strategies. 2009. Department of Homeland Security. https://ics-cert.us-cert.gov/sites/default/files/recommended_practices/Defense_in_Depth_Oct09.pdf.

Seven Steps to Effectively Defend Industrial Control Systems. 2015. Department of Homeland Security. https://ics-cert.us-cert.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Seven%20Steps%20to%20Effectively%20Defend%20Industrial%20Control%20Systems_S508C.pdf.

0 Comments